University libraries, which I have had the privilege of visiting for many years as a researcher, are full of hidden treasures just waiting to be explored. Indeed, these institutions hold substantial documentary collections, for the greatest interest of scientists, but also high-quality graphic works for the delight of art historians and lovers. The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library of the University of Toronto curates a remarkable collection of botanical and zoological graphic works executed between the 17th and 19th centuries, gathered by Lois Wiener-Lowe (1946-1985) and Daniel Lowe (1945-?)[i], a couple of art amateurs from Montreal, and offered at the university in the mid-1980s. Among its diversity, this collection includes original watercolors by renowned naturalist artists, such as Henri-Joseph Redouté (1766-1840)[ii] and Georg Erhet (1708-1770)[iii], as well as by talented but not professional artists, such as the sisters Charlotte (1759-1833) and Juliana Strickland (1765-1849)[iv], or peculiar works like the paintings on silk by Chiang T’ing-Hsi (1669-1732)[v]. Discovering this “hidden treasure” allows, succinctly, to retrace the history of naturalist drawings and paintings as well as to introduce that of the collection of these artworks, showing very specific plastic and aesthetic qualities.

Origin and evolution of natural history representations

Since the earliest antiquity, drawing has been used to represent the visible world and its components, including plant and animal specimens. The first documented botanical figurations were intended to illustrate a catalog of medicinal plants, entitled De Materia Medica, compiled by the Greek physician Dioscorides (c. 40-90 AD) in the first century of our era[vi]. Until the Renaissance, these reference images circulated widely through the use of prints. These repetitive reproductions and interpretations led to a loss of definition and precision in the representation of natural motifs and to their stylization. The quest for a return to plausible or imitative figuration began at the end of the 15th century, with artists driven by a great sense of observation such as Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) or Albrecht Dürer ( 1471-1528).

Thanks to the great European expeditions to distant lands which then multiplied, simultaneously facilitating the scientific study of exotic natural environments, the art of botanical and zoological representation developed. Thus, the drawings of the explorers, physicians and botanists Garcia de Orta (1501-1568) and Francisco Hernandez (1515-1587), respectively of Portuguese and Spanish origin, helped in disseminating images of Indian and Mexican flora, still relatively unknown in Europe[vii]. In the 18th century, the intellectual curiosity of European societies, in full transformation, and the corollary increase in knowledge also provided a matrix conducive to discoveries and their representation. The classification systems established by Carl von Linné (1707-1778) and the writing of the encyclopaedic work Histoire naturelle générale et particulière by George-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707-1788) generated ample needs for illustration[viii]. The rise of naturalist figuration, which had already begun at the end of the previous century, continued, with artists such as Maria Sybilla Merian (1647-1717) and Georg Erhet as well as with major editorial projects, like that of William Roxburgh (1751-1815)[ix]. The Lowe’s collection brings together more than sixty original watercolors related to this project as well as works to other similar initiatives.

As a matter of fact, these editorial projects were springboards for the development of natural history figuration. At the end of the 17th century, the work of various actors in the scientific and artistic worlds, all attached to the Dutch East India Company, gave rise to the publication of Hortus Malabaricus (1678-1703), a multilingual botanical compendium on Indian flora[x]. Similarly, the British East India Company became interested in the identification of Indian natural heritage, in particular through the Roxburgh project. This Scot studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and botany with John Hope (1725-1786), creator of the local botanical garden. In 1793, Roxburgh was appointed superintendent of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens, established at the initiative of the Company a few years earlier. During his twenty years in exercise, he employed local artists, trained in Indian Mughal art, to create botanical watercolors later used for the publication of Plants of the Coast of Coromande (London, 1795-1819)[xi].

The Dutch and the British were not the only ones to have developed major editorial projects in order to introduce a wide audience to new worlds. At the beginning of the 19th century, the French naturalist Ambroise Palisot de Beauvois (1752-1820) called upon different artists, including Jean-Gabriel Prêtre (1768-1849)[xii] and Jean-François Brisseau de Mirbel (1776-1854)[xiii], to illustrate a book on African flora. The Swiss naturalist and ichthyologist François Delaroche (1781-1813) also published his illustrated collection Eryngiorum nec non generis novi Alepideae Historia (Paris, 1808), still a reference nowadays. The Lowe’s collection includes some carefully preserved works executed by Prêtre, but also by other European illustrators such as the Dutchman Vincent Janz Vander Vinne (1736-1811) and the Italian artist Francesco Peyroleri (ca 1700-1766)[xiv].

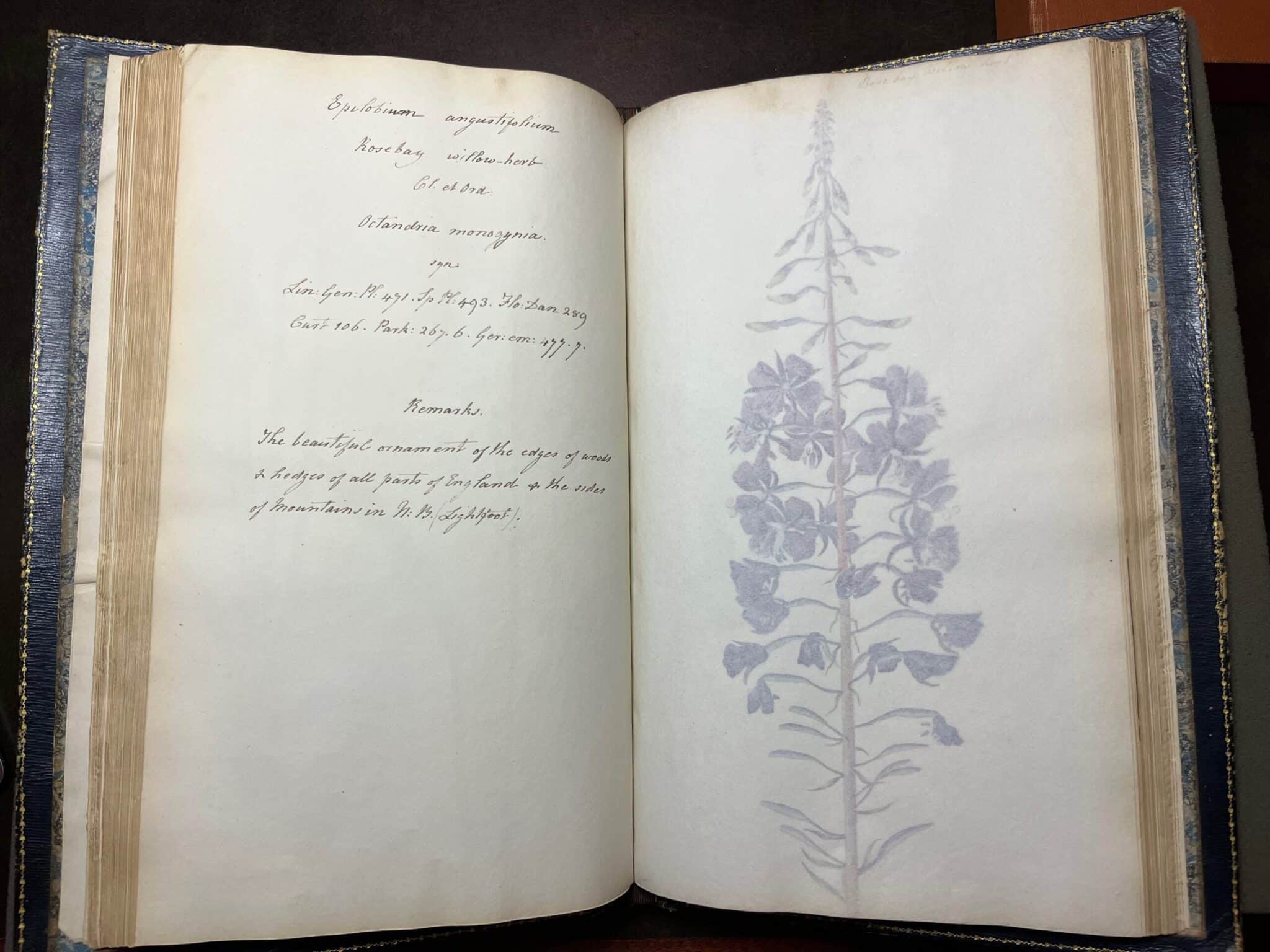

Like professional artists, amateurs played a significant role in the history of botanical art: the example of the Strickland sisters illustrates this well. Charlotte and Juliana Strickland were the daughters of Sir George Strickland (1729-1808), fifth baronet at Boynton Hall in Yorkshire. Like women of the gentry at this time, they were certainly trained in drawing as part of their education and evolved in a family and social circle which helped to develop their interest in botany[xv]. Two children of their brother Henry Eustachius (1777-1865), with whom they lived at Apperley Court from the beginning of the 19th century, were passionate about the subject: their niece Frances (1803-1888) devoted herself to botanical drawing with Charlotte and Juliana; their nephew Hugh (1811-1853) was a renowned naturalist and geologist, who married Catherine, daughter and biographer of the naturalist Sir William Jardine (1800-1874). The husband of their eldest sister Elizabeth (d. 1821) and their cousin, Strickland Freeman (d. 1821), was both a naturalist and a writer on horsemanship. Freeman was convinced that the works of Charlotte and Juliana, not only aesthetic but anatomically accurate watercolors, should be published, but felt that the engravers and colourists of the time would not be able to do justice to the originals. The publication of Delineations of exotic plants by Franz Andreas Bauer (1758-1840) at Kew in 1796 apparently helped him in changing his mind, and at his own expense he set out to publish what became Select Specimens of British Plants(1790-1803).

These albums were seen by a number of the most eminent botanists of their time, among them the Reverend James Dalton (1764-1843) and James Dickson (1738-1822), a founding member of the Linnaean Society and one of the eight original members of the Royal Horticultural Society[xvi]. Eighty-six original watercolors executed by the Strickland sisters, depicting the diversity of British flora, are part of the Lowe’s Collection.

The “art” of collecting natural history graphic works

If the need for illustration triggered the development of naturalistic figuration, the pleasure of collecting contributed in the same way to the expansion of this art. At the beginning of the 19th century, one of the first collectors of flower drawings was actually a friend of Roxburgh. John Fleming (1747-1829) was a surgeon for the British East India Company by the time Robert Kyd (1747-1793), the founder of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens, died. He was then chosen as temporary superintendent until Roxburgh was appointed in November of the same year. The two Scots shared education, profession and above all a passion for botany. Fleming gathered a collection of more than a thousand plant figurations[xvii]. Natural history artworks did not escape the contemporary enthusiasm of collectors for Asian art. This period of the 18th century was latter designated as the period of chinoiseries as this aesthetic appeal was so in various fields of art, from tapestry to porcelain. The Lowes, like their Enlightenment predecessors, were interested in Chinese naturalistic artworks, particularly the paintings by Chiang T’ing-Hsi (also spelled Jiang Tingxi), a master of the early Qing Dynasty (17th-20th century), follower of Yun Shouping (1633-1690).

According to Emmanuelle Lesbre and Liu Jianlong, this painter-civil servant-poet, who possessed a vast culture and fine judgment, developed a style that avoided excessive technical application and that shows the impact of the presence of Giuseppe Castaglione (1688 -1766), an Italian missionary painter[xviii]. Twelve botanical subjects by Chiang T’ing-Hsi, painted on silk, mounted on Japanese paper and kept in a wood panel binding, are included in the rich Lowe’s collection.

The growing attraction of art lovers for graphic works combined with the intellectual climate of the Enlightenment to favor the emergence of the first collections of botanical and zoological drawings and paintings. Until the 17th century, European collectors were more interested in pictorial and sculptural works. Important collections of old masters’ drawings began to be constituted at the end of the 17th century and in the first half of the 18th century by some French amateurs, such as Pierre Crozat (1665-1740) and Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774), and English art lovers, such as Peter Lely (1618-1680), Jonathan Richardson (1667-1745), the second Duke of Devonshire (William Cavendish, 1672-1729) or even John Bouverie (c. 1723-1750). This new penchant for graphic works must be linked to the concomitant rise in the learning of drawing – and watercolor in Great Britain – by amateurs from among the wealthiest social classes[xix]. Practicing drawing allows to appreciate the plastic qualities of the works more significantly. It is in this spirit that Richardson encourages the connoisseur, the exercised amateur at aesthetic judgment, to become familiar with graphic techniques in order to consider the art of the great masters[xx]. The quest for this connoisseurship and the development of taste as social conventions thus favored the learning of drawing and the collection of graphic works, particularly in Great Britain.

The “art” of appreciating natural history graphic works

Like many art lovers before them, the Lowes had a passion for botanical and zoological artworks. Their rich collection highlights the diversity of graphic works created between the 17th and 19th centuries, a period when the pictorial genre flourished in connection with contemporary scientific discoveries. Its composition underlines the importance of the historical links between artistic creation and the growing needs of illustration. Above all, discovering this collection increases the aesthetic appreciation, following the example of the first collectors, of the original works which gave birth to naturalist images which still widely circulate. The brief adjacent – in the Literary News and Suggestions section – bibliographical suggestions eloquently testify to the continuous current interest for this art: to be consulted to continue the discovery and to accentuate the aesthetic pleasure!

[i] Daniel Lowe was born and lived in Montreal. He married Lois Wiener in 1970. She died prematurely in 1985, at the age of 39. Dr. Lowe’s bequest to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library occured during this same period.

[ii] Henri-Joseph is the brother of the famous naturalist painter Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759-1840). He worked as a draftsman at the Muséum d’histoire naturelle in Paris and was part of the large cohort that accompanied Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) on his campaign in Egypt at the beginning of the 19th century. See Carmélia Opsomer, “Les manuscrits de Redouté, dessinateur et chroniqueur de l’expédition », L’expédition d’Egypte, une entreprise des Lumières, 1798-1801, Paris, Technique et documentation, 1999, p. 58-80. https://orbi.uliege.be/bitstream/2268/56021/1/Opsomer_1998_Exp-egypt_53.pdf

[iii] Georg Dionysius Erhet was born in Heidelberg, Germany, where he first evolved as an apprentice gardener. At the age of 23, he became a naturalist painter and was one of the first artists to specialize in the genre. Christoph Jacob Trew (1695-1769), physician and botanist from Nuremberg, relied exclusively on him to illustrate his prestigious work Plantae Selectae quarum imagines ad exemplaria naturalia Londini in hortus curiosorum (Nuremberg, 1750-1773). Settled thereafter in England, Erhet became the painter chosen by wealthy patrons to represent the botanical specimens brought back from their expeditions in the colonies, following the example of Joseph Banks (1769-1820) who entrusted him with the representation of the plants collected from his trip to Newfoundland and Labrador in 1766. See Judith Magee, Art&Nature. Three Centuries of Natural History Art from Around the World, Vancouver, Greystone Books, London, Natural History Museum, 2009, p. 199.

[iv] See text below and note 16.

[v] See text below and note 19.

[vi] Magee, 2009, p. 6. De Materia Medica constitutes one of the three essential sources on plants from Greco-Roman antiquity, with the works of Theophrastus, Historia Plantarum and De Causis Plantarum, published four centuries earlier, and that of Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia (74 AD). Dioscorides gives the properties of 827 substances, including 583 plants which are described.

[vii] Magee, 2009, p. 7.

[viii] Linné published his Systema Naturae in 1735 and his Genera Plantarum in 1752, while the Histoire naturelle by Buffon, his contemporary and fervent opponent, comprises forty-four volumes in-4°, published between 1749 and 1788, eight of which were completed. by Bernard Germain Lacépède (1756-1825) after Buffon’s death.

[ix] Magee, 2009, p. 8. On these artists, see Bert van de Roemer, Florence Pieters, Hans Mulder, Kay Etheridge and Marieke van Delft (eds.), Maria Sybilla Merian: Changing the nature of art and science, Tielt, Lannoo Publishers, 2022 as well as the quality documentary site Botanical Art & Artists: https://www.botanicalartandartists.com/famous-botanical-artists.html.

[x] Magee, 2009, p. 116.

[xi] Magee, 2009, p. 117.

[xii] Prêtre is of Swiss origin and works as an illustrator between Switzerland and France. He specializes in depicting birds, reptiles and mammals.

[xiii] Mirbel is a botanist and naturalist, pioneer of plant histology in France. He worked as steward of the gardens of Malmaison, in Rueil-Malmaison, from 1803). He was appointed professor, holder of the chair of Culture at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris in 1828.

[xiv] The Van der Vinne family was from Haarlem, and about ten members of the family practised as artists during the 17th and 18th centuries. Some members of the family were also employed in the manufacture and sale of textiles. Vincent I Laurensz. (1628-1702) is best known for his travel diaries and sketches. It is possible that some of the drawings attributed to him are by his son Laurens Vincentsz. (1658-1729), whose brothers Jan Vincentsz. (1663-1721) and Izaak Vincentsz. (1665-1740) were also artists. Three of Laurens’s children worked as painters and engravers: Vincent II Laurensz. (1686-1742), Jacob Laurensz. (1688-1737) and Jan Laurensz. (1699-1753). In the next generation Jacob’s son Laurens Jacobsz. (1712-42) became a flower painter, and two of Jan’s children, Jan Jansz. (1734-1805) and Vincent Jansz. (1736-1811), that is specifically considered here, seem to have been the last artists active in the family. Francesco Peyroleri and his son Pietro, resident artists of the Turin Botanical Garden, participated in the illustration of the major work, Floran Pedemontana, sive Enumeratio methodica stirpium indigenarum Pedemontii (Turin, 1789), of Carlo Allioni (1725-1804), the professor of botany at the University of Turin as well as director of its natural history cabinet and its botanical garden. This compendium contains the description and medicinal properties of 2813 species of plants from Piedmont, 237 of which have never been described before. It constitutes a capital work of 18th century botany because Allioni applied in an early and systematic way the new and modern Linnaean nomenclature to a vast regional botany. In this, his Flora is also important for the knowledge of the flowers of the Alps.

[xv] The nobility and the gentry constitute the highest social classes in Britain. The titled nobility is part of the peerage, which shares responsibility for government. The peerage comprises five grades which are, in descending order, duke, marquis, earl, viscount and baron. Below the peerage are the honorary ranks which include baronet and knight, two classes which bear similarities to nobility but are not generally considered as such as they do not possess hereditary honorary titles.

[xvi] See Strickland, Charlotte, Juliana Sabina and Frances, “Specimens of British Plants…, albums of original watercolor drawings”, Christie’s sale n° 5484, lot 88, London, November 2007 https://www.christies.com/en /lot/lot-281044

[xvii] Magee, 2009, p. 130.

[xviii] See Emmanuelle Lesbre, Liu Jianlong, Chinese painting, Paris, Hazan, 2004, pp. 406-407. While painting, Chiang T’ing-Hsi pursued a career as a civil servant: he was Minister of Finance, participating in the drafting of laws governing major institutions; he was an academician of the Palace of the Radiance of Letters and editor-in-chief of the classics; he was also the grand guardian of the crown prince.

[xix] See about a culture of taste and politeness in Great Britain in the 18th century, John Brewer, The Pleasure of the Imagination. English Culture in the Eighteenth Century, London, Harper Collins Publishers, 1997, p. 87-106.

[xx] Jonathan Richardson, father and son, Traité de la peinture et de la sculpture, introd. and ed. Isabelle Baudino and Frédéric Ogée, Paris, École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, 2008 (original edition1728), p. 201.