In line with this month’s museum news, here’s an article on engraving, in particular reproductive engraving also known as interpretive engraving. Although prints are less popular today than they used to be, collecting these works of art was for a long time the prerogative of most art lovers. Their attractive price on the art market meant that more people were able to buy them.

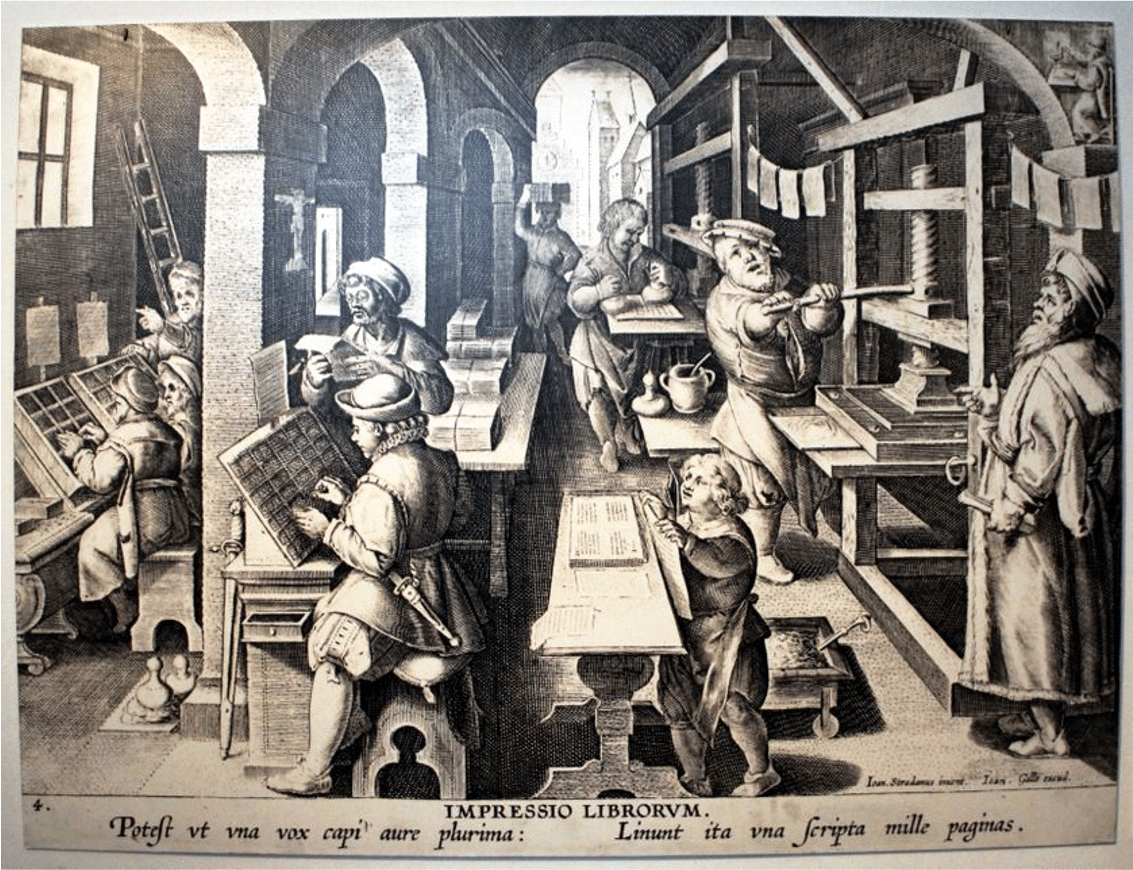

The origins of engraving can be traced back to the Renaissance, when the role of prints was paramount. In today’s world, where the circulation of images seems so natural as to no longer challenge us, it may be difficult to imagine the importance and effects of such circulation for the artists of that era. However, museums, photography and reprography were clearly not among the means of dissemination available at the time, so reproductive engraving quickly became the preferred means of circulating images of motifs and artworks. This technique helped to expand the geographical horizons of artistic influences more rapidly, giving rise to the first major European trends. It would even enable certain engravers to achieve feats of skill and produce creations worthy of being considered works of art in their own right.

The ambiguity that characterizes reproductive/interpretative engraving is a source of concern. The reproduction of images implies the notion of copying, and thus raises issues of artistic creativity and ownership. Is a reproductive or interpretative print a work in itself, or simply a pale copy of a drawing, painting or sculpture, in which all trace of creativity seems to have disappeared? And to whom should we attribute the genesis of such a work, the engraver or the artist?

With these questions in mind, this article looks at the art of interpretative printmaking in the Renaissance, developing the subject to understand the nature, importance and interest of this technique in the context of the artistic developments associated with this period of Western art history. A brief definition and history of engraving are proposed, before exploring its appeal in the artistic world of the time. This is followed by a discussion of interpretative engraving and the profession of engraver-interpreter, using the example of Marcantonio Raimondi (1480-1534), one of Italy’s most famous engraver-interpreters, who worked alongside Raphael (1483-1520).

The definition of engraving

Establishing a precise, exhaustive definition of engraving is a tricky business. The term itself refers to a mechanical means of production, but it also encompasses the artist’s creative act, the result – the original print – and the production of a mass communication medium in the form of multiple copies. In her publication on etching, Maria Christina Paoluzzi provides a technical definition of etching as “the art of hollowing out different supports by removing material. This technique consists of drawing or transferring onto a matrix […], then engraving with metal points […] and other processes in order to be able to reproduce the model in numerous copies[i] “. This definition highlights the purpose of engraving: to provide multiple copies of a single design. As for interpretative engraving, we’ll provide a brief definition here, so as to better detail its concept in the body of our presentation. This is the process by which one artist reproduces/interprets the work of another[ii] . It differs from so-called original engraving, which produces “a print resulting from the creation of an artist-engraver, an effort guided by intelligence, artistic sense and craftsmanship[iii] “.

As already mentioned, the print, also known as the proof, is the finished creation – the printed image – resulting from engraving, whatever the process used. During the historical period known as modern times, from the Renaissance to the end of the eighteenth century, two main engraving processes were traditionally distinguished: relief engraving and intaglio engraving. Relief engraving is based on transferring a design onto a plate, usually made of wood, metal or stone, by hollowing out the parts that will not be inked during printing; the design to be inked thus appears in relief above the surface of the plate. Conversely, in intaglio engraving, the motif to be inked is carved, either mechanically or chemically, into a smooth metal plate; the ink is then deposited in the carvings and wiped onto the rest of the plate. Each of these processes can be broken down into various techniques, depending on the plate material and/or the instruments used: xylography, drypoint, etching, pencil etching, aquatint, etc.

Let’s take a quick look at some more recent processes[iv] . In the early nineteenth century, flatbed printing began to develop. It is characterized by the parts to be inked in the plane of the plate, usually in stone, hence the common name lithography. It is based on the principle of reciprocal repulsion of water and fat: the design is traced with a fatty medium that retains the ink, while the unprinted parts are soaked in water, which rejects the ink. Silk-screen printing, inspired by the printing of fabric patterns long practiced in the Far East, spread to the West at the end of thenineteenth century. It uses a stencil to reproduce a design or motif.

A brief history of Renaissance engraving

This new form of expression, engraving, came into being just before the invention of movable type printing by Johannes Gutenberg (d. 1468) in the middle of the fifteenth century. Indeed, by the end of the previous century, small leaflets featuring pious images and distributed to pilgrims and worshippers were being produced using xyloglyphics or woodblock engraving[v] . Xyloglyphics thus predates typography by a long way, and a link between the two seems obvious. In the context of Renaissance humanism, which gave rise to a desire for easier access to written sources of knowledge, the production of illustrated texts on a medium that was both easier to handle and less costly encouraged the development of both techniques. The simultaneous introduction of paper as a medium for the written word also contributed to this development[vi] .

The origins of printmaking are traditionally located in the Rhine Valley and the Franco-Flemish states of the Duke of Burgundy, at the end of the fourteenth century[vii] . Very quickly in the first half of the fifteenth century, prints were also produced in Italy. Initially, woodcuts were circulated, but intaglio engravings on metal began to appear as early as 1430. By the 1450s, both techniques were in common use[viii] . According to Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574)[ix] , the first Italian intaglio prints probably originated in the niellos of a Florentine goldsmith , Maso Finiguerra (1426-1464)[x] .

The stylistic aspect of the first prints reveals the artistic characteristics of the two main geographical poles of the Renaissance: Northern Europe and its concern for imitative detail; Italy and its quest for formal beauty with reference to Antiquity. As for iconography, it was in keeping with the tradition of the period, with religious subjects predominating and allegorical and mythological themes developing. As in painting, genre scenes remain the preserve of Northern European artists[xiii] . Among the protagonists to emerge from anonymity, after the few early Master Engravers, were Martin Schongauer (1448-1491), Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Lucas de Leyden (1494-1533) in Northern Europe, and Antonio Pollaiuolo (1433-1498) and Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) in Italy[xiv] .

During the first half of the sixteenth century, the production of engravings met a specific need: to disseminate the models of the great masters of painting and sculpture. Engraving thus became “an effective means of disseminating artistic news. At the time, it was considered natural to take up an idea or composition from another artist; many second-rate painters used engravings as a repertoire of models[xv] “. This is known as reproductive/interpretative engraving.

The advantages of reproduction/interpretation engraving

Engraving was born more out of a need to multiply copies of an image than out of a desire for aesthetic research. The great masters of the Renaissance were quick to see the value of popularizing their works, both for educational purposes and to enhance their reputation. The dissemination of models through interpretative engravings played a didactic role: it enabled apprentices, craftsmen and artists to learn by appreciating the achievements and know-how of the masters. This was already advocated by Cennino Cennini (1370-ca 1440) at the end of the fourteenth century in his Libro dell’Arte (Book of Art), one of the first treatises in Western history[xvi] . This pedagogical function lasted a long time: around 1800, the Burgundian painter François Devosge (1732-1811) continued to teach from his collection of prints[xvii]. The distribution of models also ensured artists a wider reputation, beyond that established in the artistic circles of their origin or workplace. Finally, engraving is also a medium for popularizing knowledge, as “the image teaches, informs and celebrates; it facilitates the circulation of ideas[xviii] “. Today, reproductive/interpretative engravings continue to contribute to our knowledge of artistic developments, sometimes helping to identify the inventor of a composition. It also contributes to the preservation of our heritage, as it is sometimes the only witness to a vanished work.

The engraver-interpreter and his art

Print publishing became a profession in its own right at the beginning of the sixteenth century. This interest in images helped to shape the economic and social structures of the trade[xix] . In Italy, this turning point began around the time of Raphael’s practice, and engravers’ workshops rapidly multiplied, as they did in the rest of Europe. Marcantonio Raimondi, who worked with Raphael, is probably the best-known of these new Italian engraver-interpreters. He was followed by Marco Ravignano (1496-1550) and Agostino Veneziano (1490-1540). Ugo da Capri (1480-1532) perfected cameo woodcutting and produced interpretation engravings based on Raphael’s drawings[xx] . In France, the major decorative project at the Château de Fontainebleau, between 1542 and 1547, gave rise to a number of vocations, including that of Antonio Fantuzzi (1510-1550), Léon Davent (act. 1540-1556) and Jean Mignon (act. 1537-1555), all three of whom were aquafortists (etching is a process of engraving in intaglio on metal)[xxi]. Thanks to them, the innovative models of the French Renaissance crossed frontiers. As for Northern Europe, Vasari dwells at length on the Flemish-born engraver Hieronymus Cock (1518-1570)[xxii] .

The art of reproductive/interpretative engraving is more complex than it seems. The engraver-interpreter transposes onto wood or copper the work – drawing, painting, sculpture, art object – created by a renowned artist, usually at his or her request. In addition to close collaboration with the master, this practice requires real technical skill. It takes a long time to learn engraving, and just as long to create an engraved plate. Certain similarities with goldsmithing techniques, such as damascening[xxiii] , may explain why many engravers were initially trained as goldsmiths. What’s more, the transposition of a work requires the engraver to adapt his technique “to come as close as possible to the character of the works to be translated[xxiv] “. This ability to adapt from one mode of expression to another is in itself an intrinsic quality of the engraver-interpreter. Finally, even if the engraver-interpreter seems to abdicate his creativity and imagination in favor of that of the master, he does not abandon his style. Different versions or interpretations of the same masterpiece reflect the formal and expressive differences of each artist-engraver, or as the art historian Ernst Gombrich put it: “[the engraver] repeats the phrases [… of the model] with his own accent[xxv] “.

For a long time, the engraver-interpreter was perceived as more of a copyist than an artist, and his work was afflicted with negative, pejorative values. In 1821, in his Manuel des amateurs d’estampes, Musseau wrote: “Talent has its own particular stamp, and disdains the slavish walk of an imitator[xxvi] “. Yet, in the Renaissance artist’s own mind, reproductive engraving is an interpretation, not a copy: with rare exceptions, during the first half of the sixteenth century, engravers did not seek to reproduce their models exactly. Their relationship to the model was not one of emulation or rivalry. The model is the starting point for invention. [xxvii] Copy, interpreted in its strict sense of identical repetition, refers to a reproduction “executed in the same materials as the model object and under conditions that are as close as possible to those that governed the elaboration of the model object[xxviii] “. According to this definition, a copy of a print can only be another print; a print based on a drawing or painting is an interpretation.

The practice of interpretive engraving quickly raised the issue of artistic ownership, as illustrated by the Dürer-Raimondi trial. In 1506, Albrecht Dürer accused Marcantonio Raimondi of copying his xylographs by transposing onto copper seventeen scenes from the cycle of the Life of the Virgin.

According to Vasari, who recounts this anecdote in his Lives of Artists, the Seigniory of Venice, in response to Durër’s complaint, accused Raimondi of forgery and forced him to introduce his engraved monogram alongside Dürer’s[xxix] . The woodcut by Dürer presumably copied is dated 1510 (signature and date appearing on the foot of the Virgin’s bed in the Death of the Virgin panel of this cycle), making Dürer’s accusation against Raimondi chronologically impossible. However, what appears to be a preparatory drawing, executed by Dürer in pen and brown ink and enhanced with watercolor, whose format corresponds to that of Raimondi’s engraving, is dated 1503. This drawing may therefore have served as a model for the engraver-interpreter. In this case, it would be a reproduction engraving and not a copy. This conclusion must be interpreted with caution, however, as the date of the trial remains uncertain.

Conclusion

The art of reproducing/interpreting the works of masters through engraving spread rapidly across Europe from the

sixteenth century onwards, in recognition of its essential role in the circulation of models. This spread sometimes gave rise to contentious debates over the notion of ownership of invention and creativity. It was during the egihteenth century that the British artist William Hogarth (1697-1764), himself confronted with the issue of recognition of his original engravings, proposed a solution in the form of copyright (Engravers’ Copyright Act, 1735). At the same time, the rise of print collecting was accompanied by the publication of numerous guides to connoisseurship, the quality of aesthetic judgment. William Gilpin’s (1724-1804) An Essay Upon Prints, published in London in 1768, was among the first of its kind. Even today, such works continue to be made available to lovers of antique prints, such as Lorenza Salamon’s guide Comment regarder la gravure : vocabulaire, genres et techniques (Paris, Hazan, 2011). Specialized magazines such as Print Quarterly or Nouvelles de l’Estampe and L’Estampille/L’Objet d’Art also enable the most erudite to keep abreast of the latest research in the field. Collectors of antique prints can thus nurture their knowledge and acquire an expert eye.

[i] Maria Christina Paoluzzi, La gravure, Paris, Éditions Solar, 2004, p. 23.

[ii] See Ales Krejca, Les techniques de la gravure, Paris, Grund, 1983, p. 11.

[iii] Krejca, 1983, p. 11.

[iv] On these two more recent printing techniques, see Krejca, 1983, pp. 139-190.

[v] See Jan Bialostocki, L’art du XVe siècle, des Parler à Dürer, Paris, Librairie Générale Française, 1993 (1ère ed. 1989), pp. 195-225; Ad Stijnman, Engraving and Etching 1400-200, London, Archetype Publications, Houten, Hes & De Graaf Publishers, 2012, pp. 31-33.

[vi] Krejca, 1983, p. 19; Stijnman, 2012, p. 33-34; see also Monique Zerdoun, “Le papier, de la Chine à l’Occident, un passionnant périple”, in Nathalie Coural (dir.), Le papier à l’œuvre, [cat. expo. Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2011], Paris, Hazan, Musée du Louvre Éditions, 2011p. 25-40 (31).

[vii] Bialostocki, 1993, p. p. 195-225; Stijnman, 2012, p. 31-33.

[viii] Stijnman, 2012, p. 23. See also Anthony Griffiths, The Print before Photography (London: The British Museum Press, 2016), pp. 15-20.

[ix] Giorgio Vasari was a Mannerist painter of the XVIe century. He is recognized as the first art historian, having written a literary work on the painters of the early Italian Renaissance, first published in 1550, then revised and republished in 1568.

[x] Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, vol. 2, London, Penguin Books, 1987 (1ère ed. 1550), p. 72.

[xi] Jean Laran, L’estampe, Paris, PUF, 1959, p. 307.

[xii] Vasari, 1987, p. 72; Stijnman, 2012, p. 41-43.

[xiii] On artistic and stylistic considerations of the Renaissance, see, among others, Bertrand Jestaz, L’art de la Renaissance, Paris, Citadelles & Mazenod, 2007 (1ère ed. 1984) and Peter and Linda Murray, The Art of the Renaissance, London, Thames & Hudson, 1999 (1ère ed. 1963).

[xiv] See Griffiths, 2016, p. 15-20.

[xv] Ernst H. Gombrich, Histoire de l’art, Paris, Phaidon, 2006, p. 213-214.

[xvi] Cennino Cennini, Il libro dell’arte. Traité des Arts, Paris, Éditions L’Oeil d’Or, p. 56.

[xvii] The sculptor, painter and draughtsman Devosge founded the Dijon School of Drawing in 1767. He is best known as the teacher of the artist Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758-1823). See Marcelle Imperiali, François Devosge, créateur de l’École de dessin et du Musée de Dijon, Dijon, Rebourseau, 1927.

[xviii] Claude Mignot and Daniel Rabreau, eds, Temps modernes XVe – XVIIIe siècles, coll. Histoire de l’art, Paris, Flammarion, 2005, p. 262.

[xix] Griffiths, 2016, p. 15-20.

[xx] Jean-Eugène Bersier, La gravure: les procédés, l’histoire, Paris, Berger-Levrault, 1984 (1ère ed. 1974), pp. 149-150.

[xxi] See Henri Zerner, L’École de Fontainebleau. Gravures, Paris, Arts et métiers graphiques, 1969; Catherine Jenkins, Prints at the court of Fontainebleau, c. 1542-1547, Ouderkerk aan den IJssel, Sound & Vision Publishers, 2017.

[xxii] See Sophie Caron, “Hieronymus Cock, un éditeur d’estampes à la Renaissance”, L’Estampille/L’Objet d’Art, n° 495, p. 8-8.

[xxiii] The art of cold-hammering small decorative threads of one metal (silver, gold, copper) into another (iron, steel, copper).

[xxiv] Claudie Barral, L’atelier du graveur en taille-douce, [cat. expo. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Oct. 1989 – Jan. 1990], Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, p. 57.

[xxv] Ernst H. Gombrich quoted in Estelle Leutrat, Les débuts de la gravure sur cuivre en France, Geneva, Droz, 2007, p. 14.

[xxvi] J.C.L. Musseau quoted in Maxime Préaud, “Essai de définition de la copie en matière d’estampe”, Nouvelles de l’estampe, n°179-180, Dec.2001-Feb.2002, p. 7.

[xxvii] Leutrat, 2007, p. 128.

[xxviii] Préaud, 2002, p. 8.

[xxix] Vasari, vol. 1, 1987 (1ère ed. 1550), pp. 306-307.